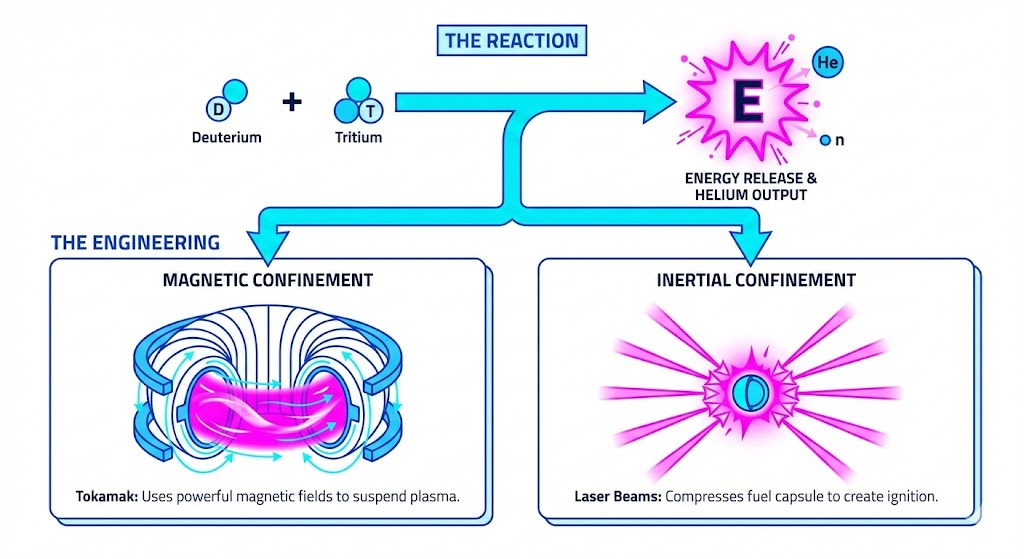

Nuclear fusion is the fundamental physical process that powers the Sun and other stars, whereby two light atomic nuclei join to form a heavier one, releasing enormous amounts of energy. Unlike nuclear fission, which splits heavy atoms generating long-lived radioactive waste, fusion exploits hydrogen isotopes (deuterium and tritium) to produce helium and neutrons, offering nearly unlimited and carbon-free energy potential. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), this reaction generates four times more energy per kilogram of fuel than fission and nearly four million times more energy than burning oil or coal.

Key Takeaways

- Process: Union of light nuclei (Deuterium + Tritium) into helium.

- Output: Massive thermal energy ($E=mc^2$) with zero CO2.

- Safety: No risk of uncontrolled meltdown.

- Status: Ignition (net gain) demonstrated, but commercialization still requires engineering development.

What is nuclear fusion and the physical principles

To fully understand this technology, it is necessary to analyze plasma physics. For nuclear fusion to occur on Earth, hydrogen isotopes must be heated to temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius. Under these extreme conditions, matter transitions from a gaseous state to the plasma state (the fourth state of matter), where electrons separate from atomic nuclei.

The nuclei, being both positively charged, tend to repel each other due to electrostatic force. Only extremely high temperatures and pressures allow them to overcome this barrier (Coulomb Barrier) and get close enough for the strong nuclear force to prevail, fusing them together and releasing kinetic energy.

How nuclear fusion works: confinement methods

Since no solid material can contain plasma at 100 million degrees, scientists use two main methods to “confine” the reaction. The success of nuclear fusion on an industrial scale depends on the optimization of these techniques.

- Magnetic Confinement (MFE): Uses powerful magnetic fields to suspend the plasma inside a vacuum chamber, typically toroidal (doughnut-shaped) called a Tokamak. This is the approach used by the international ITER project in France. Superconducting magnets prevent the hot plasma from touching the reactor walls.

- Inertial Confinement (IFE): Uses powerful lasers or particle beams to compress and heat a small fuel capsule (target) in a few nanoseconds. The rapid implosion creates the density and temperature conditions for ignition. This method was used by the National Ignition Facility (LLNL) in the USA to achieve the first net energy gain in 2022.

Strategic advantages and the ITER project

Global interest in this technology stems from its structural advantages over current sources. Firstly, fuel abundance: deuterium can be extracted from seawater, while tritium can be produced in situ (breeding) during the reaction itself.

In terms of safety, the process is inherently safe. A fusion reaction is difficult to maintain; any disturbance or technical failure causes the immediate cooling of the plasma and the cessation of the process, eliminating the risk of catastrophic accidents like Chernobyl or Fukushima. Furthermore, it does not produce high-activity radioactive waste requiring geological storage for millennia. Currently, the ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) consortium represents the most complex engineering effort in human history, aiming to demonstrate the scientific and technological feasibility of fusion as a large-scale energy source within the coming decades.