Synthetic biology is an interdisciplinary scientific field that combines engineering and biology principles to design and construct new biological parts, devices, and systems not found in nature. Unlike traditional biology, which studies living organisms as they are, this discipline aims to redesign them for useful purposes, treating DNA as programmable code. According to the National Human Genome Research Institute, its primary goal is to make biological engineering more predictable and standardized.

Key Takeaways

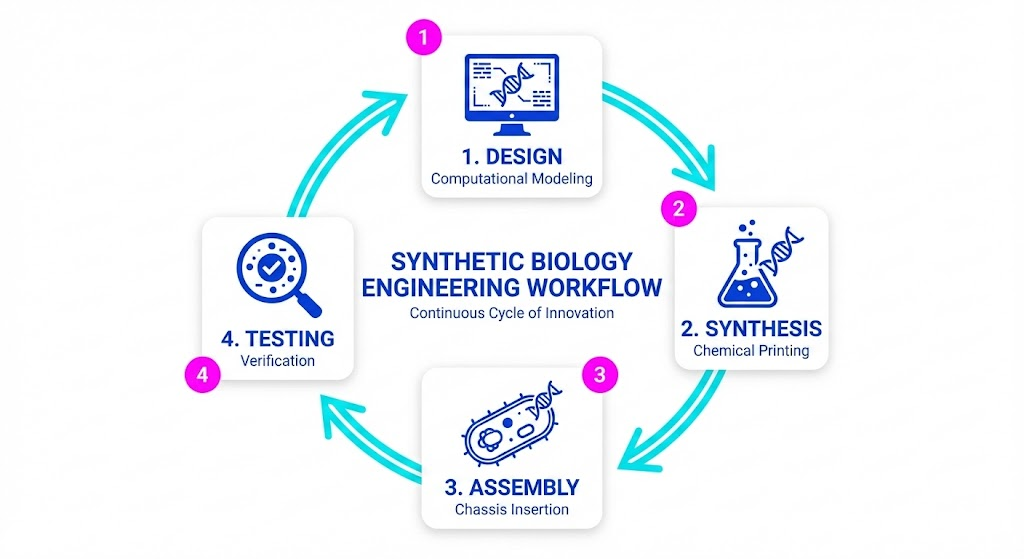

- Engineering Approach: Applies the “Design-Build-Test-Learn” cycle to living systems.

- Standardization: Uses interchangeable genetic parts (BioBricks) to build complex circuits.

- Global Impact: Revolutionizes critical sectors such as pharmaceuticals, sustainable energy, and agriculture.

What is synthetic biology and how it differs

Often confused with genome editing, synthetic biology represents a further step in the manipulation of life. While genome editing (like CRISPR) typically acts by cutting or repairing small portions of DNA in an existing organism, synthetic biology involves assembling long strands of DNA, often chemically synthesized from scratch, to insert entire metabolic pathways or new functional traits into a host organism (chassis).

Scientists in this field do not just modify; they build. The approach relies on creating libraries of standardized biological parts, known as functional components, which can be assembled into “genetic circuits” capable of performing logical operations within the cell, similar to electronic circuits.

How the design of biological systems works

The operational process follows rigorous engineering principles: abstraction, modularity, and standardization. The typical workflow involves:

- Design: Computational modeling software is used to design DNA sequences that code for specific functions (e.g., producing an enzyme or reacting to an environmental stimulus).

- Synthesis: The designed DNA is not extracted from nature but chemically printed (DNA synthesis) in the laboratory.

- Assembly: Synthetic fragments are inserted into a “chassis” organism (such as the bacterium E. coli or the yeast S. cerevisiae).

- Testing: The organism is analyzed to see if it performs the programmed function.

This method allows common microorganisms to be transformed into efficient and scalable “cell factories.”

Main applications of synthetic biology

The adoption of synthetic biology is generating tangible impact across various industrial sectors, offering solutions to complex global problems:

- Medicine and Pharmaceuticals: The semi-synthetic production of artemisinin (a potent anti-malarial drug) via engineered yeast has stabilized global costs and supply, reducing dependence on plant extraction.

- Biofuels and Green Chemistry: Redesigned microorganisms convert agricultural biomass or waste into advanced fuels and ethanol, offering renewable alternatives to fossil fuels.

- Biomaterials: Biotech companies use bacteria to produce high-performance materials, such as synthetic spider silk, which is biodegradable and stronger than steel, or petroleum-free plastics.

- Agriculture: Development of crops capable of fixing nitrogen autonomously, drastically reducing the need for polluting chemical fertilizers.